Addressing construction's major pain points

Authors

Jordan Kirrane

View bioThere are multiple pain points that are repeating themes in the construction industry: cost of materials, cost of labour, defects, time pressures and achieving quality. These issues also frequently get cited as a counter argument in the discourse around improving sustainability outcomes.

A solution for achieving better sustainability outcomes while also addressing many – if not all – of the pain points is adoption of modular prefabrication coupled with effective use of digital design and delivery technology.

There are many advantages to utilising prefabricated modules in construction including:

* Consistent high-quality factory produced components

* Quicker construction times and reduced labour requirements

* Increased construction safety

* Reduced waste

* Reduced material emissions

* End of life material reuse opportunities

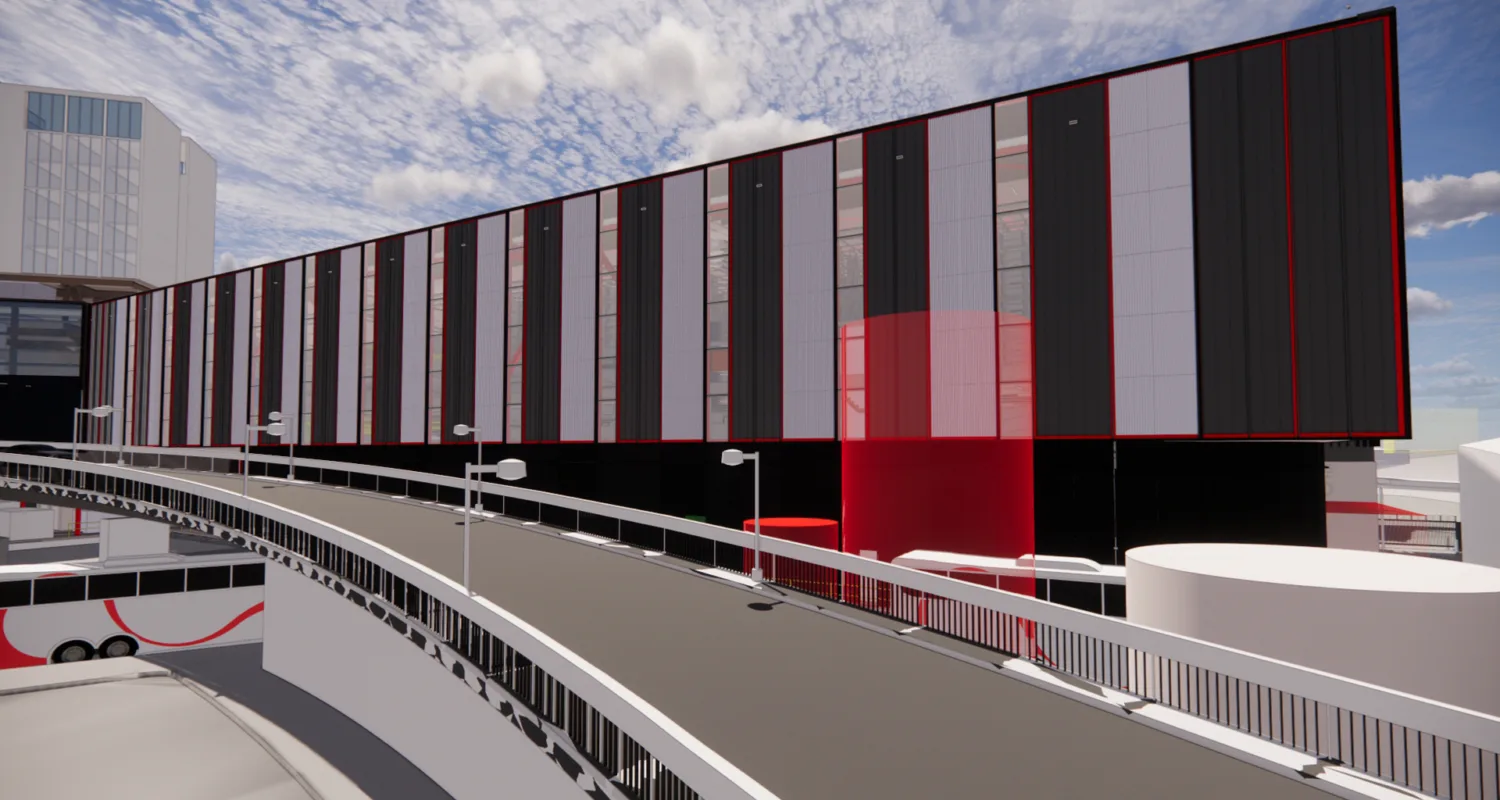

The precision and build quality achieved in modular construction allows for greater choice of materials that can be used. From a sustainability perspective, engineered timbers including cross-laminated timber (CLT), glued laminated timbers (glulam) and laminated veneer lumber (LVL) are exceptionally well-suited to an efficient construction approach. Each has its place – CLT for walls, floors and facades; glulam for internal walls and partitioning; and LVL for structural members.

For high rise applications, hybrid cassette-type solutions such as steel/CLT combinations can deliver the required load bearing for floors, and for facades in buildings above 25m fire safety provisions can be satisfied with performance solutions approaches including encapsulation of exposed timber and sprinkler installations.

Mass timber construction approaches often result in lower embodied carbon than traditional ferro-cement construction.

It all sounds very straightforward, and there have been exemplar projects that have shown timber can be constructed far more quickly and with a much smaller on-site workforce than conventional in-situ construction. There is also the obvious safety dividend of building methods that engineer out the requirement for workers such as steel fixers or form workers undertaking tasks on an exposed edge at height.

So why isn’t mass timber modular construction the new normal? Aside from concerns including perceived fire risks, or client preferences for business-as-usual approaches, or lack of available local product, there is one major obstacle to successful widespread adoption.

It’s an obstacle also encountered where projects use precast concrete as part of a hybrid construction approach.

Precast can have a lower embodied carbon footprint, result in less waste and deliver similar safety and speed dividends to engineered timbers. Being made off-site means quantities can be tightly controlled and managed, green concrete mixes and recycled reinforcing can be used, and the final product can be designed and fabricated to exact design specifications.

However, getting the optimal outcome from design through to fabrication and on-site installation requires one crucial linking element - all elements of the build both on and off site need to be tightly controlled and coordinated to ensure smooth onsite assembly. This is best achieved through using digital tools to connect the dots and ensure precision of production and assembly.

Lagging on tech adoption is the weakest link

As an industry, we still have not achieved effective use of building information modelling (BIM) and the associated applications throughout the value chain. This is the weakest link, and it contributes to offsite not always living up to its potential.

For example, one of the most common defects found during a delivery program is tolerances are not what they should be. Where specifications and design are produced in disconnected information silos, an error can occur at any point, and depending on where that point is, can become magnified.

The result is what was designed, what was delivered and how the kit of parts is being installed frequently do not match up exactly. So, we get gaps and overlaps, or angles that don’t quite meet as they should and so forth.

That then means either additional work to rectify the issue or - as is sadly fairly common - the imperfection is left as is and the final building contains numerous small defects, some of which in the case of gaps will reduce the thermal performance and may lead to other issues such as water ingress.

How BIM helps close the lifecycle circle

The other consequence of project teams not utilising BIM to its full capability is buildings reach end of life and there is no clear pathway for re-use of the component materials. It’s almost ironic given concerns around the cost of materials for new builds that they are assigned no end-of-life value when planning a project business case.

BIM can be used to help rectify this. Ideally, any building should be approached as a kit of parts that can be assembled, disassembled and reassembled for the lifespan of those materials. BIM design and information about the material can be linked through the use of infrared labelling on major material items that connects to the BIM model – just like the labels on a shelf in a shop link into the digital inventory and ordering system.

Then at end of life, the information of what a specific item such as a façade panel, structural beam, acoustic tile or fenestration assembly can be retrieved during disassembly and the item can be productively redeployed. This is a win for the planet and also a win for addressing the cost of new construction materials.

The BIM application can also reduce waste, rework and rate of defects onsite where it is partnered with laser-guided assembly onsite. Use of this approach means every element of both onsite construction and onsite construction is accurate to the detailed design. There’s another cost saving and a time saving through reducing the need for rectification when tolerances are not accurate.

Overall, the key to addressing the big pain points is putting greater investment of time, expertise and technology at the front end – design and planning – to save time, cost and waste at the delivery and handover end of the value chain.

This article was first published at Sourceable